Siembamba 2014

Artist Statement

Lullabies are ancient and universal, sung to calm young children because of their soothing and repetitive rhythm (Opie I 1951:6). The term Siembamba is used in a number of Afrikaans poems as well as this poem ‘n Nuwe liedjie op ‘n ou deuntjie, translated in English as ‘a new song on an old tune’1 . Written by C Louis Leipoldt, at first it seems as if the child is hushed to sleep by his mothers soothing lullaby but ironically, the child is dying in his mother’s arms in a concentration camp during the Anglo-Boer War1. (Viljoen 1998:577). My exhibition title Siembamaba relates to this verse as it has since been used in Afrikaans lullabies, although the term2 is also used throughout the world and has roots as far back as the 17th century (Alberts 1962:62). Its origin remains vague, and its meaning is elusive, shifting from culture to culture and from context to context2 (Alberts 1962:62).

My artmaking relates to the ongoing and worldwide violence against women and children, and I address this issue by exploring aspects of the historical trauma experienced by the Boer women in these concentration camps. This work has grown out of my own experiences with domestic abuse.

Two important influences in my research were the work of contemporary artists Joseph Beuys and Gerhard Marx.

The ‘war’ continues

The United Nations Population Fund (UNPF) Gender Theme Group (1998:5) defines gender-based violence as “violence involving men and women, in which the female is usually the victim”, derived from unequal power relationships between men and women. It includes, but is not limited to physical, sexual and psychological harm (including intimidation, suffering, coercion, and/or deprivation of liberty within the family or within the general community) (Groenewald 2006:13). UNPF has indicated that gender-based violence, especially in developing countries, is widespread and common (Groenewald 2006:14). In South Africa, violence against women is rated the highest in the world (Faul 2013).

Still Images

Conversations with my mother provoked further research. My theoretical exploration consisted of studying a literature review of Leipoldt’s poetry, investigating the term Siembamba, and undertaking historical research of the Anglo-Boer war. I visited the National Women’s Monument in Bloemfontein and various concentration camp graveyards, collecting data and photographing these sites. The images for the video and photographs came from the graveyard at Balmoral in Mpumalanga. The research I undertook and the resulting artmaking processes proved cathartic. My chosen materials and mediums serve as metaphors for transience and loss due to the abuse of war – historical and domestic. My exhibition work consists of five parts: an installation cage holding a blanket and maps printed on canvas; a video titled Siembamba which features a performance, photographs; printed copies of the lullaby poem Siembamba; and maps printed on paper. The blanket and maps hold special significance and will be discussed here in more detail.

The rusted barbed wire cage is the exhibition installation site where two significant tangible symbols – the destructed blanket⁴ and the printed canvas maps – are integrated. It stands as a metaphor on several levels, including history and war; captivity and confinement; and loss of self-identity and isolation.

The concentration camp blanket references aspects of the physical and psychological degradation undergone by the Boer women in the camps. Often the only possession a Boer woman in the camps had was her blanket. Over time this became worn, yet also provided protection; ultimately it could be used as a shroud.

Maps printed on canvas of sites from different countries indicate historical sites of annihilation and/or concentration camps. The canvas references the fabric of the concentration camp tents. Another set of paper prints of these maps indicate sites of more contemporary conflict.

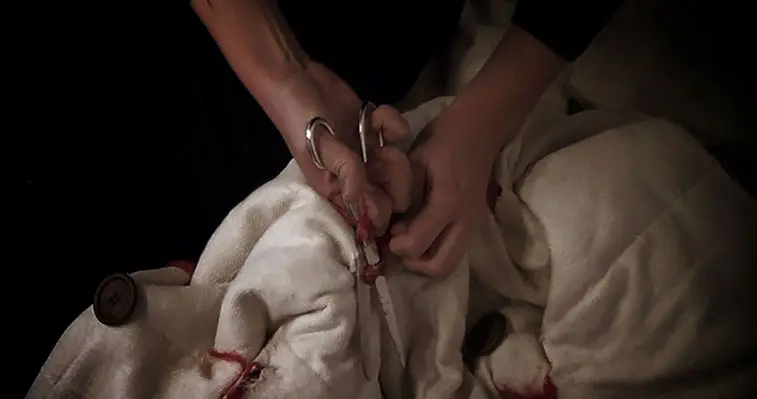

In the video performance, Siembamba, a Boer women holds the blanket on her lap, cutting and destructing it, acts which symbolize the experience of suffering and loss. The tension between the usual expectation of feminine mending and sewing and the rawness inherent in the cutting and destruction refers to the helplessness of women and children in situations of conflict and war. Sound is also an important factor in the video. The audio is provided by a studio remixed and layered recitation by women and children of ’n Nuwe liedjie op ‘n ou deuntjie, suggesting collective suffering. Photographs of the burnt grass and mist in the graveyard, taken during the early morning hours of winter, capture a sense of the scorched earth, the cold and the desolation.

‘n Nuwe liedjie op ‘n ou deuntjie was translated into 14 languages and transferred lithographically onto handmade paper. While inking and wetting, the delicacy of the flesh-coloured paper mimicked the fragility of the body and its potential for deterioration. The printing process itself is symbolic, as the pressure required to print each mark, and the repetition inherent in creating more than one print, both speak of the ongoing physical and emotional marks made by continuous violence and abuse.

My work had its roots in the experiences of the women and children in the concentration camps of the Anglo Boer War, and has grown into a comment on the continuation and universality of domestic abuse. My intention is that this exhibition should highlight this issue and hopefully encourage dialogue and debate.